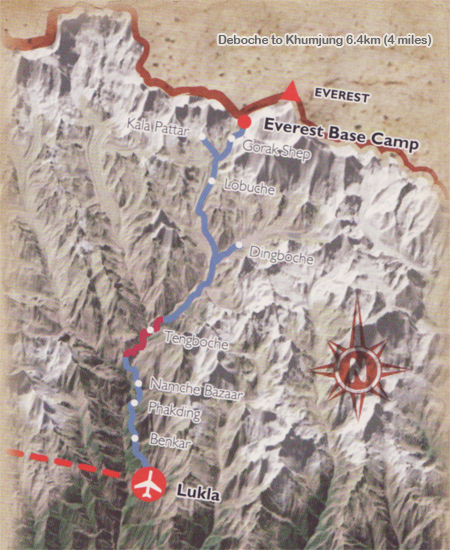

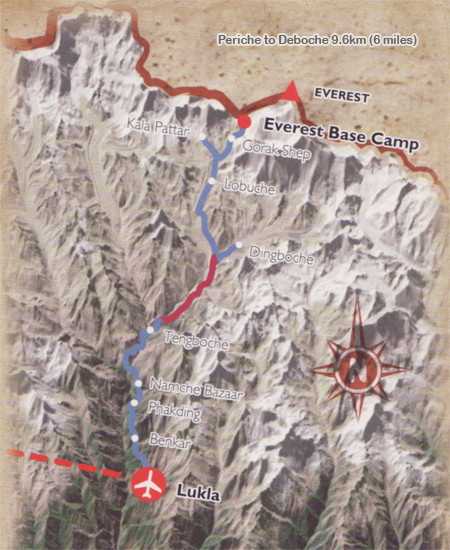

The next morning we walked up the stone pathway through the white rhododendron tunnel for the last time. At the top of the hill in Tengboche, we made friends with another dog, a female this time, who became our pet for the day. Dovile named her Fergie.

Fergie trotted along side us down the pink rhododendron-lined switchbacks to the river, where we stopped at the end of the suspension bridge again for some tea. Stacy and Dovile mentioned wanting to take her home.

“I don’t think any of us could provide as good a home for her as she has here.” I said.

“She’s free to run these mountain trails all day and it appears as though she has plenty to eat. It’s a dog’s paradise.” I was a little jealous. Okay, maybe a lot jealous.

DK made good his promise and gave the little boy who lived there the red cricket ball. The boy, glad to have some playmates, also played with Ele and Dovile with a piece of wood that through the magic of imagination became a plane. He brought out another toy to show us, a plastic rabbit on three wheels. The fourth was missing. DK asked Bibak the word for rabbit.

“Kharayo, kharayo, kharayo,” he repeated.

Before we left, Bibak threw Stacy on his back and pretended he would carry her up the hill on the other side. We were sure he could have done it without much trouble.

On the way up to Khumjung we passed a tree nursery established by the Himalayan Trust. Sir Ed could see the direction Nepal was headed and sought to mitigate the environmental impact caused by increased tourism to Everest.

With its rapidly increasing population, primitive agriculture, and steep terrain, Nepal has the most serious erosion problem of any country in the world, and the problem worsens as more forests disappear in the scouring of the land for food and fuel; in eastern Nepal, and especially in the Kathmandu Valley, firewood for cooking (not to speak of heat) is already precious, brought in by peasants who have walked for miles to sell the meager faggots on their backs. The country folk cook their own food by burning cakes of livestock dung, depriving the soil of the precious manure that would nourish it and permit it to hold water. Without wood humus or manure, the soil deteriorates, compacts and turns to dust, to be washed away in the rush of the monsoon.

Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard

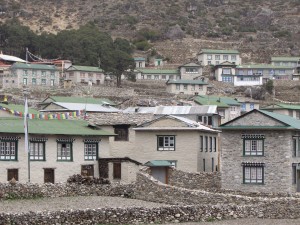

Once up the hill on the other side, we cruised along a relatively smooth trail into Khumjung. The most striking thing about Khumjung was the entire town appeared to be color-coordinated, in contrast to the kaleidoscope of colors present everywhere else we’d been. Every sheet metal roof was green. Did they have some sort of high-mountain homeowners association enforcing the rule?

Fergie was still with us when we got to our lodging. The Hidden Village was also beautiful, with lots of stone and wood. Our room had a spectacular view of the village. We all enjoyed veggie momos and spring rolls for lunch to make it easier for them to prepare. DK went into the kitchen to help, the rest of us, considered unclean both literally and spiritually, were not permitted. Dovile and Stacy went outside to play with the dog while we waited. After lunch Fergie had disappeared… maybe to head back home, wherever her home actually was.

Every yard in town was fenced with a rock wall and the passages between the walls were narrow. DK expertly lead us through the maze to get to a monastery at the foot of the mountain across town from our lodge.

On the way, I can’t really explain it, it felt like I moved into a dark cloud. The energy got really heavy. Later when I tried to rationalize it, I thought maybe the altitude had finally brought up some muck that had been plaguing other people in their dreams. I’ve also been accused of being an empath so perhaps the energy I picked up might not have been mine. Whatever it was it hit hard and hit fast.

We passed some cute little baby cows or yaks or yak-cows and I didn’t care. DK pointed out a community water spring that Sir Ed, who focused a lot of his attention on Khumjung, had put in for the community. This seemed really sad to me, that the people couldn’t even get water for themselves.

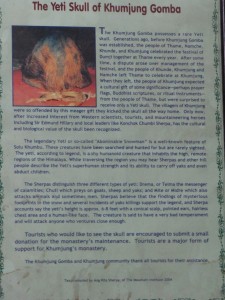

We entered the monastery and took off our shoes. They appeared to be restoring it, the building was in nowhere near as good condition as the one in Tengboche. Was this because of fewer tourist rupees? Once inside they unlocked a case with a supposed yeti skull. The somewhat barbaric story of how it came to be there didn’t improve my mood.

We sat down in a circle and DK started to talk more about the Nepali culture and how women were supposed to appear sad at weddings as part of the tradition. Historically girls were married off in arranged marriages, and would leave their families at a young age for a life of servitude. While this isn’t necessarily the case today, brides still pretend to reflect the sadness of their ancestors.

Funny how marriage tends to be a better deal for men, yet even today many women still use it to measure their self worth.

An old man came in and hissed me off the bench where I was sitting. Fuck, I just sat on a religious artifact didn’t I? This is a huge no-no. Without being conscious of what I was doing, I had plopped down on one of the benches reserved for monks. I skulked over to where the others were sitting, completely ashamed and embarrassed. It was about that point I began to become aware of the dark cloud I had wandered into, because I don’t normally attract that kind of experience. What was going on?

We pulled on our shoes and headed back downhill. Still in my funk, I was annoyed with all the shallow American chit-chat. You’re missing the real Nepal, my shadow whispered. We were in the first and only place that was somewhat out of the “tourist tunnel” and yet insisted on keeping the tourist bubble around us with our conversation and our activity. I had to get away.

The second we got back I made a beeline for our room. Maybe the others were going to go play volleyball now, I didn’t know and didn’t care. Like Dumbledore’s crazy sister I felt whatever this was about to come exploding out of me. Where would I go? The top of a nearby hill was my first choice, but now I was afraid I’d be intruding on some other forbidden holy land like a kitchen or an old bench. Maybe upstairs? I eyed the staircase and then looked down the hall at some doors on the end. They opened onto a balcony. This would do for now. I settled into a meditation pose and just breathed.

Though it took a while, eventually the darkness lifted. Sitting on that balcony I was able to observe a day in the life of the village without being seen. Well, that’s not true, one monk on the path saw me and we watched each other curiously as he walked, but most of the other locals were oblivious. A man swept the front of his shop for what seemed like hours. A nearby chicken scratched a safe distance from the old-fashioned broom. Young men and women moved quickly and cheerily up the path. Old men moved slowly. Someone used a megaphone to send a message to the other side of town. Clouds began to form in the river valley below and moved slowly up to the edge of the village. Baby potato plants grew in the sandy soil beneath me.

Still conscious of being unclean, I went back to the room long enough to get my nail clippers. Amanda was upstairs and I asked her what time we should meet for dinner. Not for a while, so I went back to my balcony to spend more quality time with Nepal.

I was cheerful and otherwise back to normal again by dinner. Since I left the group rather abruptly and never returned for the volleyball game, DK asked how I was doing. Fine, now. I said I’d been conscious of being the tourist, and wanted to see the town without being seen. He seemed to understand and had the good grace to leave it at that.